I made a choice. A gamble, maybe. Truist Park is in Cobb County, 10 miles northwest of downtown Atlanta and the former homes of the Braves, Turner Field and Fulton County Stadium. The ballpark was about a half hour walk from my hotel, separated by a shopping mall, a shopping center and a mixed-use commercial district. It being August in Georgia, I wanted to cut down on sweat time but didn’t want to pay the outrageous garage rates near the park. Instead, I grabbed a free spot in the mall lot, halfway between the hotel and the ballpark and just a few hundred feet from the sign that said “PARKING FOR MALL CUSTOMERS ONLY.” I stayed in the car for a minute until the security guard drove away, then locked up the Mazda 3 and crossed my fingers on the way to the pedestrian bridge that would take me to the ballpark.

One bridge led to another bridge which spilled into one of the overpriced parking garages. The space between the entry and the exit stairs was reimagined1 as a giant advertisement for Ford, featuring a show model 2024 Bronco in “velocity blue.” There was little to no signage — the shiny new SUV was doing all the talking — but if there were it would probably have read, “Your illegally parked car was towed and crushed into a metal pancake. Can we interest you in this 2024 Bronco in velocity blue?”

I left my mid-century modern motel in Miami on Tuesday morning and drove north on I-95 to my mid-century modern motel in Savannah, making only brief stops for gas and pee breaks over the seven hour trek. I had driven a touch more than 13,000 miles by this point of the journey to all 30 Major League ballparks, and about 4,000 of those in the last 10 days. I was seeing yellow, rhythmic, passing lane markers in my vision whether I was in the car or not. All of my dreams were about driving. No stretch of highway was unique to me anymore, including this one.

It was humid as fuck when I got Savannah, so I cranked down the air conditioning and hung out in my room at the Thunderbird Inn, a quirky, retro motor lodge on the outskirts of the Savannah College of Art and Design campus. Though much smaller in size and population, Savannah is something like the New Orleans or Austin of Georgia: a weird, artsy, shiny bubble in a sink full of dirty dishwater. I knew I was going to need dinner and I would regret not finding an interesting and independent place, preferably within short walking distance. Reddit, don’t let me down…

On the promise of fried duck wings, I made my way to Crystal Beer Parlor, a 90-something year old Savannah staple. Fifteen minutes on foot through the city’s gorgeous historic district and the swampy air had me sweating, despite trying to stay in the evening shade. The entrance to this classic corner bar is around the back, and I popped in behind a party of 10 that probably made the trip over from Hilton Head expecting to just pop in and be seated. No such luck: Crystal is first-come, first-served seating, no reservations, and they were packed on this Tuesday night. Whomp whomp for them, but I still had to patiently wait for my own seat to open up at the bar.

The couple sitting next to the service rail spotted my Toledo Mud Hens hat while I was ordering a pint, poised to strike the moment a patron gave up a stool. They asked if I was from Ohio and told me they met at Bowling Green State University. I responded with an enthusiastic “Ay Ziggy Zoomba”2 and we started chatting about our alma mater until a bar stool fortuitously opened up next to them. As the conversation turned to other northwest Ohio topics, they mentioned that they had good friends in my original hometown of Clyde. It would be too much of a small world coincidence if they knew any of my family, but I had to ask and, of course, they didn’t.

Shortly after they left, another solo flyer who introduced himself as Matt bellied up to the bar next to me. We got to talking, I mentioned I was from Ohio and he said, “my mom’s from a little town in Ohio. Ever hear of Clyde?”

What are the chances, 600 miles from home, that I’d end up sitting at a bar talking to completely unconnected people with ties to Clyde, Ohio?

We talked for a while over a few rounds of local beers. As things were starting to wind down, a couple opened the front door to leave, the first time it had been opened since I got there, only to discover the torrential downpour soaking the streets. Matt and I decided to stay for one more round to wait it out.

The bar crowd thinned out once the rain stopped and we said our goodbyes. I still had most of a beer left, so I stayed and finished it while talking to the bartender, who was from Detroit and a fellow baseball fan. We reminisced on our visits to old Tiger Stadium on the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, watching the free-swinging sluggers of the early ‘90s like Cecil Fielder, Mickey Tettleton and Rob Deer.

It was a combination of the nostalgia, the coincidence and the booze that blinded me to the fact that I was the very last customer at the Crystal Beer Parlor. All of the staff, including the Motor City bartender, were doing their closing chores while I sat there totally oblivious. Once it finally dawned on me, I apologized, paid my tab, left a hefty tip and ventured out into the misty Savannah night.

I slept in at the Thunderbird, hitting the road for Atlanta around 11 a.m. Much like Miami, this was just going to be a pop-in for the game, a night of sleep and an early call to the asphalt the next morning. As much as I would’ve liked to explore a little more of the city, I had set my travel schedule around making it back to Ohio in time for my mom’s 70th birthday, which was just a couple days away. No time to lollygag around Atlanta.

After getting caught in some of downtown ATL’s famously snarled traffic, I got to my hotel near Truist Park around 4 p.m. on Wednesday. I had a choice to make: drive nine hours the next morning and sleep in my own bed Thursday night for the first time in six weeks, or take a detour for lunch at Myles’ Pizza Pub, a fixture of my college years at Bowling Green that had been transplanted to Greenville, South Carolina. The altered course would add about three hours to my trip, which probably meant staying the night somewhere North Carolina, maybe Charlotte or Asheville?

If you guessed that the lure of unique pizza nostalgia and the adventure of exploring one of America’s best beer cities would be impossible for me to deny, well, maybe the version of me you know from these missives isn’t the real me. The real me wanted to go home. The real me wanted to see my wife. The real me wanted to see if my cats would recognize me. The real me wanted to cook dinner. The real me wanted to play a guitar. The real me wanted to park the Mazda 3 in the garage and let it rest.

With that decision made, it was getting close to gate time and I was determined to get the bobblehead promotional giveaway. I cruised around the Galleria specialty shops and event center across the freeway from Truist Park, looking for a secret parking hack. Finding only controlled-access garages at a minimum of $25 a pop, I went across the street to the Cumberland Mall, parked the car for free, said a little prayer, headfaked toward the Cheesecake Factory for the benefit of mall security and diverted course toward the ballpark.

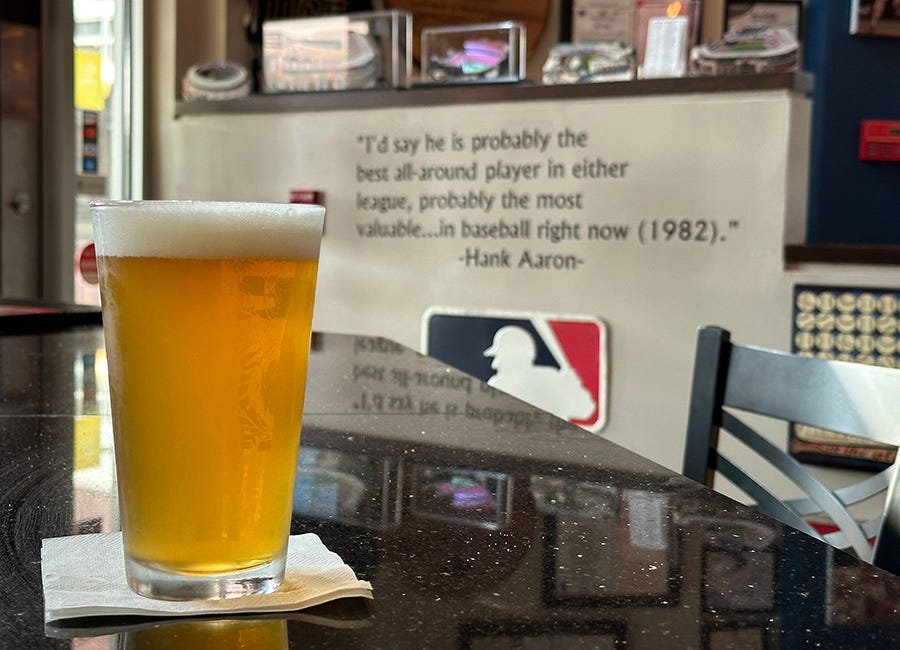

First stop, Murph’s, a tavern at the Galleria owned by Dale Murphy, who spent the bulk of his 15 seasons with the Braves patrolling the outfield at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, earning two National League MVP awards, five Gold Gloves and seven All-Star Game appearances in the process. Thirty years after hanging up his spikes, he’s slinging beer and pub grub across the highway from Truist Park at an easy-to-miss mall in the shadow of a bigger mall. I had time for a single Murph’s Golden Ale, made for them by StillFire Brewing, before heading to the game.

Opened in 2017, Truist Park was the first facility purpose-built for Major League baseball erected in a suburb since Angel Stadium in 1966.3 It replaced Turner Field, located just south of downtown Atlanta at the intersection of I-20 and I-75/85, which began its life as Centennial Olympic Stadium for the 1996 games. The building was designed to be immediately converted to a ballpark for the 1997 season. After about 15 years, the Braves announced their intention to move away from downtown, citing six critical detriments to Turner Field:

Traffic gridlock that dissuaded fans from driving to games.

A lack of parking spaces in close vicinity and the inability to secure more.

No light rail mass transit service to the ballpark.

The site "doesn't match up with where the majority of our fans come from."

The team did not control commercial development around the ballpark.

The park was reaching the end of its functional lifespan, having been “value engineered” to last only 20 years before major renovations were required.

Points 1-3 are valid: traffic in Atlanta SUCKS, especially on the freeways that cut through downtown near the former ballpark. More parking spaces can accommodate game traffic, but not mitigate it the way public transit can. The city has since started building a bus rapid transit (BRT) line adjacent to the Turner Field site — now known as Center Parc Stadium, the home of Georgia State football — connecting downtown and South Atlanta. I have plenty of feelings about BRT, something that my city of Columbus, Ohio is pushing in lieu of light rail construction, namely that something is not always better than nothing. I’m not saying that *this* BRT line in Atlanta won’t help people, but it wouldn’t have helped keep the Braves at Turner Field.

That’s because of points 4 and 5: the team didn’t want to stay in Atlanta proper because they prefer to cater to wealthier fans. The poverty rate among residents in the neighborhoods surrounding Turner Field was about 40%. In Cobb County, it was 8%. Developers wouldn’t touch commercial property around Turner Field, but they were actively building up the suburbs, looking to cash in on the expendable incomes of the population fleeing the city. The team claimed at the time that the new ballpark site in Cumberland was “near the geographic center of the Braves' fan base,” which is hard to read as anything other than a dog whistle.

Traffic and transit concerns can be dealt with in a strong public/private partnership. Issues of poverty, wealth inequality and upward mobility are obviously trickier: the sad fact of capitalism is that businesses will chase money where it is plentiful rather than try to build up a customer base among the less fortunate. The nail in Turner Field’s proverbial coffin, however, was actually a birth defect.

Building a structure to accommodate 75,000-100,000 track and field fans is something that happens nearly every Olympiad. Designing that structure to suit a lasting purpose beyond the ceremonies and games is relatively easy for other countries: most of them become soccer stadiums for national teams and popular professional clubs. But this is America. We play “real” football here. The Atlanta Falcons didn’t need a new stadium: the Georgia Dome opened a few years prior to the ‘96 games. That left the Braves, itching to get out of the concrete donut stadium they had played in since moving from Milwaukee to Atlanta in 1966, as the new tenant of Centennial Olympic Stadium.

However, planned conversion and planned obsolescence were equal parts of the stadium’s design and construction. “Fast, good, cheap… pick any two,” as the saying goes. To get the stadium built on time and as inexpensively as possible, the architects and contractors made concessions that dramatically shortened the practical longevity of the facility. By the time structural renovations were required, the team estimated a price tag of $150 million to keep the facility usable, plus another $200 million to enhance the fan experience. With the city of Atlanta unwilling to contribute after approving the construction of a new home for the Falcons to replace the Georgia Dome, the fate of Turner Field was sealed.

In Truist Park — originally SunTrust Park — the Braves addressed all six of their major issues. Haha, just kidding. The park is directly adjacent to the I-75/I-285 Perimeter interchange, aka the Cobb Cloverleaf, one of the busiest freeway interchanges in the country.4 Traffic in the area is so heavy that first pitches are scheduled anywhere from 7:15 to 7:35 p.m., as opposed to standard starts of 6:40 to 7:05 around the league, just to accommodate the congestion and delays.

Cobb County’s CobbLinc offers no rail transit, and Atlanta’s MARTA light rail does not extend to the northwest suburbs. MARTA offers a solitary bus line from Midtown Atlanta to the Cumberland Mall, with the closest stop about a mile from the ballpark. Cobb County has a bus and BRT route serving Midtown that drops off at The Battery, the commercial district outside the ballpark. The county also offers two free but relatively infrequent circulator buses that connect The Battery and the park to the adjoining malls, offices and parking lots.5

It doesn’t take an Einstein or a Hawking to realize that these paltry transit options encourage fans to drive to Braves games, not to offer alternatives. That strategy also helps to keep the poors away by making it exceptionally difficult and time consuming for those fans to attend games. To further hammer it home, there are some 14,000 parking spaces spread across 19 lots in the direct vicinity of the stadium, several of which offer full validation of their exorbitant fees if you spend enough money at businesses in The Battery. So, basically, the traffic still sucks, there’s not really an alternative, but buy a few extra overpriced margaritas and you’ll get free parking before you drive home drunk. Cool plan.

Atlanta Braves Holdings, Inc. owns not only the Atlanta Braves™, but also The Battery Atlanta™,6 the 2.25-million-square-foot mixed-use “neighborhood” adjacent to Truist Park. Home to chain stores and restaurants galore, The Battery bills itself as “The South’s preeminent lifestyle destination.” I guess if your lifestyle consists of watching ambitious local restaurateurs get squeezed out by franchised, fast-casual concepts, window shopping for boutique electric vehicles without troublesome political associations, watching washed-up rock bands take a break from the county fair circuit to play at the Coca-Cola Roxy™ by Live Nation, and keeping your age-inappropriate, Gen Z alpaca haircut7 continually fresh, then maybe you would consider living here instead of just visiting.

This is the sad, dystopian future of baseball: the game is no longer enough to be the attraction. It’s no longer enough to be a fan, support the team, buy a jersey and a beer or two at the ballpark and then go home. The owners need to extract every possible dollar from your wallet, not only directly through ticket, merchandise, concession and parking sales, but also indirectly through their astroturf neighborhoods where all of the tenant businesses kick a share of profits up to the club. These team-controlled commercial districts are supposed to evoke the organic, fan party atmosphere of Wrigleyville or Lansdowne Street outside of Fenway, but it just strikes me as another mall, across the freeway from another mall, that’s across the street from yet another mall (where I parked my car for free.)

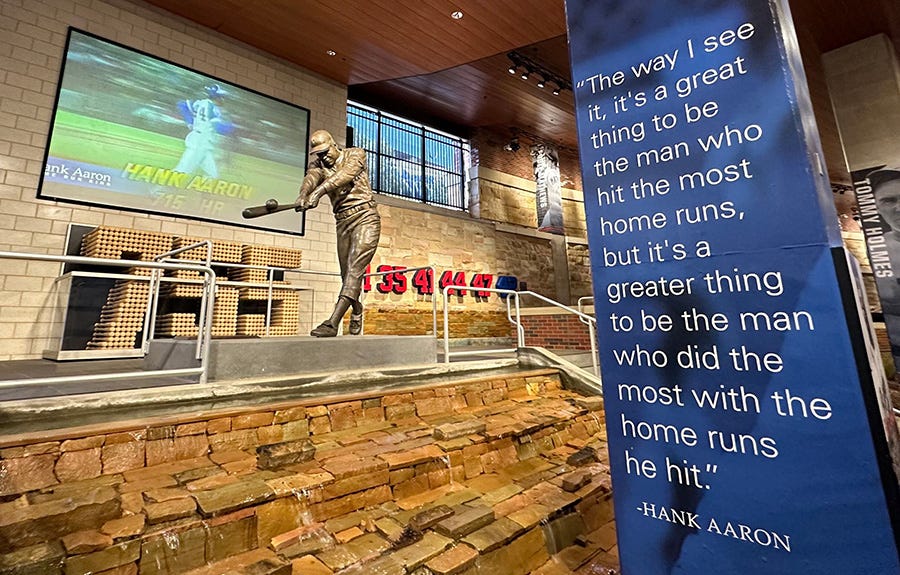

Once you’re inside Truist Park, it’s a marginally better experience in that a baseball game will be played, but the bombardment of advertisements is pretty much constant. I went in via the first base gate, adjacent to the Delta SKY360° Club private entrance, and grabbed my Ozzie Albies promotional bobblehead sponsored by NexGard Plus. From there, I made my way over to the Braves Monument Garden presented by LG to check out the team’s hall of fame and history museum. The larger-than-life statue tribute to Hank Aaron and his 755 major league home runs dwarfed the informational plaque highlighting the team’s Native American partners8 hung in a far flung corner of the exhibit.

Ford may have secured the parking garage advertising space, but Chevy ponied up for the prime real estate inside Truist Park. Just outside the foul pole down the left field line, a Colorado pickup and a Traverse SUV take up about 600 square feet of main concourse space, blocking a prime view of on-field action. Luxury brand Lexus is appropriately installed on the suite level, with a show model on display outside of the bougie Xfinity Club entrance. It’s probably worth mentioning that when designing the stadium, someone made the decision that it should be possible to get a full-size sedan up to the second level of seating. It wouldn’t shock me if the upper decks are vehicle-accessible too.

I wandered around the park while waiting for my friend Joseph to arrive, strolling by the Home Depot Clubhouse, the Coors Light Chop House and the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta kids’ interactive zone before I got the text to meet him at the Terrapin Taproom. There’s not much local business representation inside the park, save for Terrapin. Founded down the road in Athens, the brewery built its brand for a decade before Molson Coors acquired a majority stake in 2016. Just days before my visit, the “cannabis lifestyle company” Tilray announced that they had purchased Terrapin and three other craft beer brands from Molson Coors, just as they had invested in eight brands that Anheuser Busch/InBev had decided they no longer had a use for. Thanks to Molson Coors’ divestiture of the brewery and the nature of their sponsorship deal at Truist Park, the Terrapin Taproom is no more as of the beginning of the 2025 season, with the Blue Moon Beer Garden moving from its third deck rooftop patio to the much more valuable real estate two levels below.

Listen, I know I’m beating this to death, but I wouldn’t have to if all of these advertisements, product placements and corporate sponsorships weren’t so utterly distracting. Baseball has been used as a marketing vehicle for everything from alcohol to zucchini9 over the past 150 years, and it’s never been particularly subtle. I don’t know if we’re all just getting dumber and companies feel the need to repeatedly bash what’s left of our brains in with their blunt force messaging, or if we’ve just accepted that any fleeting joy we can still get out of this world needs to be interrupted every 90 seconds by the sponsors who keep the dopamine trains running on time.

I had purchased a single general admission ticket in the left field nosebleeds for this game months in advance, not knowing if I’d have any company. When Joseph told me he could make it, I scoured the secondary market for a deal on a pair with a better view. We ended up in section 325, overlooking home plate, for about the same price per seat as my GA seat including egregious Ticketmaster fees. From this vantage point, the barrage of advertising mercifully subsided, save for the Harrah’s Cherokee Casino’s logos painted on the grass in front of the dugouts and the video board activations that lit up between innings. The view beyond the outfield walls is primarily that of the corporate office buildings across the freeway, making it feel as if someone dropped a big league ballpark in the middle of downtown Tulsa or Toledo: not unimpressive, but hardly iconic. The lack of scenery draws your attention back to the team on the field, a quality product that Atlanta has consistently delivered, much to the chagrin of other National League East squads, like the visiting Philadelphia Phillies.

The injury-riddled Braves, missing star players Ronald Acuna Jr., Austin Riley, Spencer Strider and bobblehead honoree Ozzie Albies, trailed the division-leading Phillies by seven games coming into the contest. After taking the first game of the series the night before, Atlanta sent veteran southpaw Max Fried to the mound in an attempt to gain some ground. Fried kept the powerful Phillies offense off the board for the first five innings, protecting the 2-0 lead provided by Orlando Arcia’s homer in the fourth. In the top of the sixth, Philadelphia small balled their way to two runs and a tie score on a single, a double, a fielder’s choice and a sacrifice fly. Atlanta would turn the ball over to the bullpen in the top of the eighth, summoning Joe Jimenez who promptly gave up a double to rookie left fielder Weston Wilson. The next two Phillie batters hit long fly balls, with Wilson advancing 90 feet on each and scoring the go-ahead run. Fireballer Orion Kerkering and trade deadline acquisition Carlos Estevez would shut down the Atlanta offense in the final two innings, preserving the win for Philadelphia.

Joseph and I left our vista level10 seats relatively early on, opting instead to take in the game from a few of the branded viewing areas around the park. Before we found an optimal rail at which to post up in deep center field, our attention was drawn back to the field for a between innings sponsor activation. “Beat The Freeze,” a promotion paid for by RaceTrac convenience stores, pits one average fan in a footrace around the outfield warning track against The Freeze, a mysterious character clad in ski goggles and a light blue spandex bodysuit. Starting at the left field foul pole, the fan is given about a five second head start before The Freeze starts his run. In almost every showdown, The Freeze closes the distance before passing the fan within a few dozen yards of the finish line. The surprise of being caught by The Freeze often leads to the fan contestant tripping over their own feet, unceremoniously faceplanting in the rough dirt path between the outfield grass and the fence. It shouldn’t be such a shock: the man behind The Freeze’s goggles — men, plural, actually — are track and field sprinters Nigel Talton and Durran Dunn. Not to mention that the “Beat The Freeze” races have been run at almost every Braves home game since 2017. In 2025, you know what you’re getting into when you accept the challenge. Unless you’ve got the skills to back up your swagger, you’re going down, figuratively or literally.

They say if you watch enough baseball games, you’ll see something you’ve never seen before. They also say that even a blind chicken finds a kernel of corn now and again. Somewhere on this spectrum is what happened on Wednesday, August 21, 2024, when a dude in khaki shorts beat The Freeze by five feet.

Joseph took off before the end of the game, so I decided to climb all the way up to the 400 level and watch the last inning or so from the general admission sections where my original ticket was. Despite the fact that it was pushing 10 p.m. on a weeknight, despite the fact that enough fans had left to beat the traffic that there were ample seats elsewhere, despite the fact that the Phillies were showing no signs they would relent, there were still fans up in the cheap seats hanging onto hope. This is what the ballpark experience should be: worrying only if your boys have some ninth inning magic left, rather than if you spent enough money to validate your parking. And if team owners want to quantify success, might I humbly suggest using wins and losses as the measure vs. red and black.

The heavy flow of pedestrian traffic I was in when I left Truist Park dwindled the further I went, some veering off for post-game revelry in The Battery and others finding their cars for the drive home. By the time I got to the pedestrian bridge that led to the Cumberland Mall, I was all alone. This was the moment of truth: would my attempt to game the capitalist parking system in suburban Atlanta be successful, or would I spend the rest of my night springing my trusty Mazda 3 out of impound?

It was there. Of course it was there. I was worried about mall security?

For once, my dreams weren’t about driving, even though I had a nine hour trip ahead of me from suburban Atlanta to my home in Columbus, Ohio. I made a surprise drop in at a work happy hour event just north of Cincy to the utter shock of my co-workers. Worth the diversion for the reaction, but I was more than ready to be back home. It had only been 11 days since I dropped Erin off at the airport in Oakland, but it felt so much longer. Even the last two hours behind the wheel seemed like an eternity.

Four days to relax, and then back at it. Point the car to Boston and New York. Finish the tour. Go the distance.

NEXT GAMES:

Toronto Blue Jays at Boston Red Sox, Thursday, Aug. 29, 7:10 p.m. EDT, Fenway Park

St. Louis Cardinals at New York Yankees, Friday, Aug. 30, 7:05 p.m. EDT, Yankee Stadium

I’m giving the architects some big benefit of the doubt here that “lifestyle marketing area” wasn’t in their original parking garage drawings.

“Ay Ziggy Zoomba” was an unofficial fight song when I went to school at BG, but was granted official status in 2013. While it’s fun and catchy, it doesn’t hold a candle to “Forward Falcons.” You wish your college had a fight song as good as either of these.

-OK, you can make a very thin argument that Yankee Stadium II and Citi Field, both opened in 2009, are “suburban” in that they are not in Manhattan. However, they were built adjacent to and to replace Yankee Stadium I and Shea Stadium, respectively, so those were established sporting sites and both still technically in the city of New York, so get out of here with that weak shit.

-You could make a somewhat stronger argument for SunLife Stadium, formerly Joe Robbie Stadium, in Miami Gardens, Florida, but it was built as a multipurpose stadium and was home to the NFL’s Dolphins six years before the Marlins came to town.

-You could make an even stronger argument for Arlington Stadium, which opened in 1965, built on spec to lure a baseball team to the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex. Eventually, the Washington Senators would relocate and play their home games in Arlington as the Texas Rangers starting in 1972. Arlington Stadium has since been replaced twice, both times in Arlington, first by The Ballpark in Arlington in 1994, then by the Rangers’ current home and most recently built MLB ballpark, Globe Life Field, opened in 2020.

But, ironically, not even the most congested in metro Atlanta. That title belongs to the the I-85/I-285 interchange, colloquially known as Spaghetti Junction and formerly known as Malfunction Junction before a major redesign in the 1980s.

There is one more public transit service, provided by the Cumberland Community Improvement District. The Hopper operates two autonomous mini-shuttles: one that takes you from the Galleria office buildings to Murph’s, and another that carries you 500 feet across the pedestrian bridge over I-285. According to their website, the Hopper service was complimentary through December 2024. Can’t wait to see how much they start charging for that 500 foot ride in 2025.

On their own website, they are consistently inconsistent about which rights marker to use: The Battery Atlanta® or The Battery Atlanta™. Either way, nothing screams “soulless, corporate piece of shit” like proudly waving these legal appendages as battle flags.

Full disclosure: a version of this has been my go-to haircut since before Zoomer kids were born. It’s nice to see my style gain mainstream acceptance, though I doubt many of them are hitting up their stylists to dye a few hundred random hairs gray.

The plaque specifically references the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, one of three federally recognized Cherokee tribes, with educational information about their tribal territory, language and the history of Cherokee stickball. As you may expect from a team that named itself after the exclusively white but Native-cosplaying Tammany Hall, its commitment to tribal partners is capricious and self-serving.

Currently framed in my basement is a 1950s vintage crate label for Safe Hit Texas Vegetables, packed and shipped by Gulf Distributing Company of Weslaco, Texas.

I’m not sure if I’m supposed to capitalize “vista level” here or not. There’s the Lexus Level in the 200s, obviously capitalized, and the lower level in the 100s, not capitalized. “Vista” implies a view, which there isn’t much of here. Maybe it’s supposed to be the VistaPrint Level?

Just so we're clear here, Truist Park is the necessary extension of Braves Corp Holdings shopping mall/Real estate bonanza?

Also sweet Christmas you said this one was gonna be a heater but good God. You were clearly channeling Lancaster Ohio's most famous son and I salute you for it.