I spent a grand total of about 17 hours in Miami. The way the schedule worked out, I would have just enough time to catch a game and get a decent night’s sleep before I had to point the Mazda 3 northward. If you were hoping for a report on my experiences in Miami’s legendary club scene, you are out of luck. Truth is, despite embarking on this two month road trip to all 30 Major League ballparks, I’m pretty much a homebody. Not a hermit, mind you, but more than comfortable issuing a “thanks, but no thanks” toward a night on the town without a hook that really excites me.

At this point, it had been six full weeks since I last slept in my own bed, easily the longest stretch I’d ever gone, blowing past my old record from the three weeks I spent in Germany between my junior and senior years of high school. In just three days, I’d be back home again, a thought which began to dominate my mind and influence my behavior. I was less interested in exploring or seeking out unique experiences. Like a baseball team out of contention for a postseason berth, I was just playing out the string. I started thinking that I might be ready for this to be over.

I blazed through Alligator Alley — the stretch of I-75 that spans South Florida over the Everglades — as fast as I could, knowing that I was going to be cutting it a little close for a 6:40 first pitch. Once you get this far down the peninsula, the only population density is along the coasts. Between Naples on the west and Fort Lauderdale on the east, there are about 75 miles with barely a trace of human settlement. Only a relative handful of Florida’s 23 million residents live here in the wetlands, mostly indigenous Miccosukee and Seminole tribes, as well as backcountry dwelling Gladesmen. It’s a hard and relentless way of life, depending on the swamp for your survival, but home is where you make it, as these people have for hundreds, even thousands of years.

It’s not a lifestyle I’m cut out for, being among the softest of the soft, speeding forward in mobile air conditioned bliss through the hot, humid Florida summer afternoon. From the highway, I spotted Hard Rock Stadium — better known to ‘80s and ‘90s kids like me by its original name, Joe Robbie Stadium, and known to almost no one as Land Shark Stadium, its Jimmy Buffet-inspired, Anheuser-Busch sponsored moniker that it held for eight months in 20091 — the former home ballpark of the Florida Marlins from 1993 to 2011. Ultimately, the polyonymous football stadium in Miami Gardens was deemed unfit for baseball, prompting the team to move to their new home 12 miles to the south and change their name to the Miami Marlins.

I drove through Little Haiti, the area known as Lemon City prior to the 1970s and a portion of which is currently being reimagined by developers as the Magic City Innovation District. The neighborhood has been home to Black and Afro-Caribbean communities since the 19th century, which, as it does in virtually every American city, makes it a prime target for gentrification and cultural annihilation.

The New Yorker, my home for the evening, is one in a row of retro-chic, Miami Modern hotels and motels in the city’s Upper East Side neighborhood, sandwiched between Little Haiti and Biscayne Bay. I checked in around 5 p.m. and had just enough time to admire the hotel’s mid-century touches — my room’s necessary2 was decked out in pink tilework, much like the time capsule bathroom of my own vintage 1957 home in Columbus — before heading out for the game. Miami’s MetroRail system doesn’t yet serve Little Haiti, so I’d have to drive 15 minutes to the closest station to take the train, which would be about a 10-15 minute trip. After deboarding, it would be about a 20 minute walk to the ballpark. An hour out in muggy Miami didn’t sound too appealing, so I decided to beat the heat, drive 20 minutes and park in one of the garage fortresses that surround loanDepot park.3

As distinct, iconic and instantly recognizable as mid-century Miami Modern architecture is, the ballclub looked not to the past when designing their new home, but to the future. Every ballpark that had been built in the 30 years prior had taken at least some inspiration from the retro-classic marvel that is Oriole Park at Camden Yards in Baltimore, opened in 1992 and still one of Major League Baseball’s most awe-inspiring venues. The “jewel-box with modern amenities” concept had become almost cliché as the formula was repeated over and over, with only the retractable roof ballparks in Phoenix, Seattle, Houston and Milwaukee significantly deviating from the norm. Miami was set to break the mold.

loanDepot park — or, as it was called from 2012–2020, Marlins Park — is the first of its kind: a contemporary, neomodern ballpark that is a functional piece of art, representative of its environs and evocative of the future. No retro-classic tropes, no cookie-cutter symmetry, no safe, staid subtlety. The building is striking from the outside, flanked on the east and west by colorful, palm tree lined plazas. It towers over the Little Havana neighborhood, its glass facades reflecting the city back onto itself. Inside, the retractable roof provides a needed respite from the intense Florida sun and a safe haven against Miami’s frequent rain. Despite many enclosed ballparks feeling both unnaturally spacious yet somehow confining, a dichotomy that causes an unnerving level of cognitive dissonance in me, loanDepot park’s capacity — just 36,742, second smallest in the majors4 — actually makes the game experience feel much cozier than other indoor parks. The windows along the east side beyond the outfield walls are retractable like the roof, allowing for a breeze when they’re open, as well as plenty of natural light and views of the downtown Miami cityscape whether they’re open or closed.

The Marlins are kind of the opposite of their in-state neighbors, the Tampa Bay Rays, in that they won two World Series championships in their first 11 seasons of existence before floundering in mediocrity for a decade and a half, whereas the Rays spent their first 10 years as cellar dwellers before becoming a perennial playoff team. The Marlins shoehorned themselves into a football stadium ill equipped for their purposes before building a flashy new field, while the Rays have played all of their home games to date in a park built for baseball but obsolete from day one.5 What the two Florida clubs have in common is that neither of them draw fans whether they’re playing well or not: the Marlins have been in the bottom five teams in average attendance every year for the past quarter century with the exception of 2012, the year Marlins Park opened. Miami went 69-93 in their first season at their new home, which ended with a massive fire sale to cut player payroll. Once the novelty of their new digs wore off, there wasn’t much left to keep fans coming out to support an uninspiring brand of baseball.

I bought my parking in advance but waited to get my ticket from the box office. With the game being on a Monday night and the Marlins near the basement of the National League, there was no reason to splurge on a ticket: I could get my bleacher or ‘bleed seat on the cheap and give myself free upgrades throughout the game. I walked up to the window and asked for the least expensive ticket in the joint. For just $14 with tax, I was in the door and on my way to section 135, row 4, seat 15, under the scoreboard in center field, about as far away from the action as you could be, despite the section being called the Home Run Porch. Perfection.

Speaking of deals, Miami has some of the best food and drink specials in the big leagues. At a few designated stands sprinkled around the park, you can indulge in the 3 o 56 menu, which includes a $3 hot dog and a $5 can of macro beer among other offerings. For a discount glizzy, it was shockingly good, better than some of the full price dogs I’ve had at other parks this summer. This may be the only big league field where one could conceivably attempt the 9-9-9 challenge — nine innings, nine hot dogs, nine beers7 — without taking out a second mortgage or selling a kidney to finance it.

It was Bark at the Park night in Miami, and a handful of the 7,318 paid attendance — I’d guess fewer than half of those actually showed up — brought their dogs to hang out in the concourse under my section. Local animal shelters and rescues also brought adoptable pups to the game, reminding me that getting a new dog8 was on the agenda once I was finished with this trip. Our home just hasn’t felt quite right since our sweet girl Ramona passed in April.

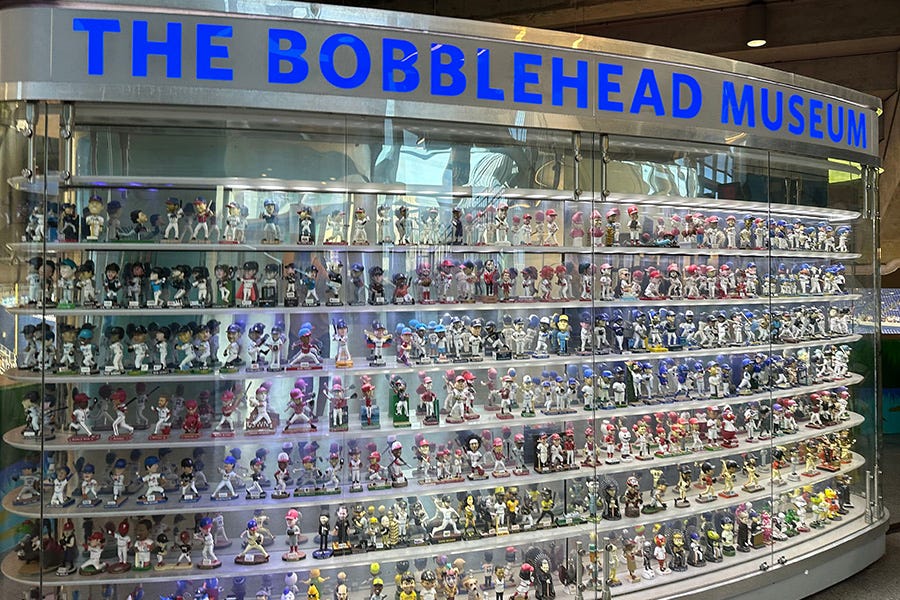

There are a lot of fun little distractions sprinkled throughout the main concourse.9 The Bobblehead Museum features several hundred of the collectible toys, with representatives from all 30 MLB teams on display.10 And yes: the whole thing moves ever so slightly so that the heads bobble. Neat. There’s a tribute to Marlins superfan Louis Mendez, aka “The Pin Man,” with his famous leather vest and hat, every square inch covered in enamel pins, a celebratory suit of armor and proclamation of his undying love of the team. Mendez never got to see a game at loanDepot park — he passed away in December 2010 at age 70 — but his memory lives on here. You can hone your influencer chops at the “Beisbol is Life” mirror selfie station, listen to fans play their horns and drums to hype up the crowd,11 or get food from one of the many baseball-themed concession stands like Oppo Taco, Fowl Pole and Intentional Wok. One thing you can’t do from the concourse is access the main team store: the only entrance to that is from the west plaza outside the ballpark. There are plenty of smaller merch shops and stands inside the building, but it always seems odd to me when the biggest collection of team gear isn’t available to ticket holders during a game.12

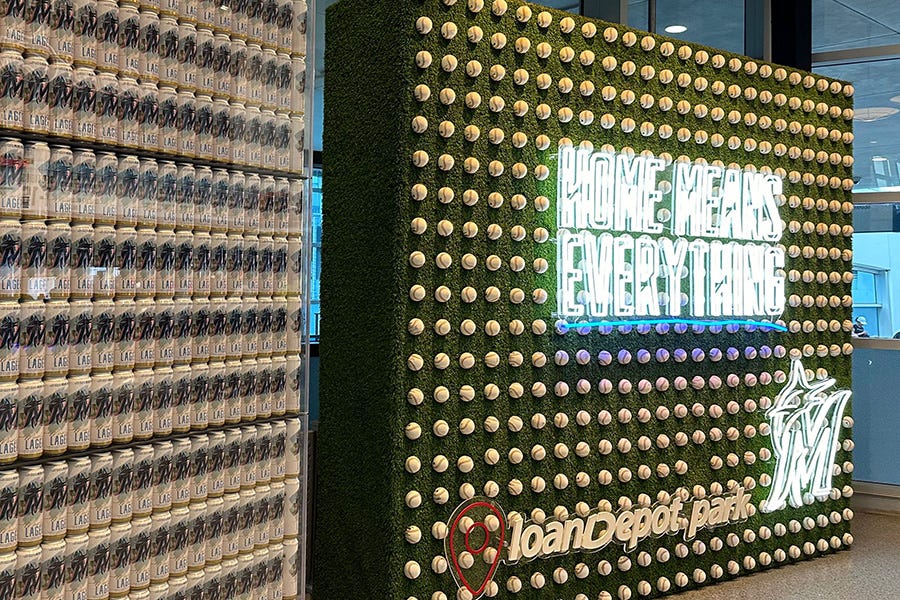

Next to the Biscayne Bay Brew Hall entrance in the concourse behind the bougie section 14 seats, there’s a corporate slogan illuminated in bright white neon: HOME MEANS EVERYTHING. It’s a marketing campaign for the ballpark’s sponsor, loanDepot, a non-bank, direct-to-consumer mortgage lender, designed to put a feel-good face on a company that identifies you as a potential home buyer, originates a loan for the biggest purchase you’ve ever made, then sells your brand new lifetime of debt off to another lender. But goddamn, that glowing sign hits hard when you’re all alone and you haven’t been home in six weeks.

You’re never going to believe this, but when I climbed up to the Home Run Porch way out in center field in search of section 135, row 4, seat 15, somebody was sitting in my seat. Ten minutes before first pitch, it looks like there are fewer than 1,000 people in the ballpark to this point, and somebody’s sitting in exactly the seat I had just purchased a half hour prior. What were the chances? Rather than evict them, I just plopped down into one of the many open seats in the section and watched as the pre-game ceremonies rolled on. I texted Nick from Arizona, the guy I met the day before at the Rays game who was about to conclude his tour of all 30 Major League ballparks, a feat that it took him several years to accomplish. He had really great seats: field level, section 10, right behind the visiting Diamondbacks dugout, about four rows back. I told him I’d try to connect with him at some point, but I was going to watch the first couple of innings from the nosebleeds.

Miami starter Adam Oller and Arizona hurler Brandon Pfaadt traded zeroes for the first two innings, each bending but not breaking, allowing only minor traffic on the bases. I decided it was time for dinner and a seat upgrade, so I hit up The Change Up — yet another baseball-themed concession stand — down in the right field corner. The concept behind The Change Up is a rotating menu of chef-driven takes on traditional ballpark food, often incorporating an unusual ingredient or emphasizing a specific type of cuisine. On this day, it was four different varieties of donut patty melts. I chose option #3: a beef patty topped with bacon, cheddar cheese and chipotle ranch, panini pressed inside a glazed donut. I grabbed a couple napkins and posted up on the rail behind section 2 with two outs and the bases loaded full of Diamondbacks in the top of the third inning.

Arizona’s rookie catcher, Adrian Del Castillo, had been called up to the big club a couple weeks earlier, making his Major League debut on Aug. 7. He was faring pretty well against his first taste of big league pitching, going 9-for-29 with two homers, the second of which I saw the previous day in Tampa.13 Del Castillo was born in Miami, played high school ball for Gulliver Prep in Miami, was drafted as a 36th rounder by the Chicago White Sox in 2018, but turned down a contract to play college ball at the University of Miami. In 2021, the Diamondbacks selected him in the second round of the draft and gave him a $1 million signing bonus. He worked his way up the minor league levels, blasting homers every step of the way until finally getting the call. And here he was, back in his hometown, a big leaguer at last.

I had just taken a bite out of my donut patty melt when Del Castillo ripped a ball down the right field line, hooking ever so slightly, landing just inside the foul pole at the back of section 1. This was the first time all season that a ball had been hit anywhere near me. I was so shocked I didn’t know what to do. I dropped the sandwich out of my sticky fingers and slowly turned right toward the empty section where the ball settled to rest. The only person closer to the ball was the usher patrolling the aisle between sections 1 and 2; he leisurely strolled over, picked it up and gave it to a kid, no shit, in section 3. If I had shown even the least bit of alacrity — or even situational awareness — I probably could’ve had a nice souvenir that would spark nostalgic joy whenever I looked at it. Why *this* ball, you ask? Because three pitches later, Adrian Del Castillo launched a grand slam 414 feet over the center field wall, in front of his family, his friends, his high school and college coaches and teammates, all on their feet in sections 8 and 9 behind the visitors’ dugout, hooting and hollering for their hometown hero.

The Fish came back, nibbling away at Arizona’s lead, narrowing it to 5-4 by the end of the sixth inning. Del Castillo would put the Diamondbacks up for good in the top of the seventh, scorching a single to right field that plated two more runs. By this point, I had made my way over to the third base side of the park, grabbing an empty seat toward the back of section 20 just under the club level overhang. It also happened to be directly under an air conditioning vent. Sweet, sweet air conditioning.

Del Castillo led off the top of the ninth inning, and I found myself a seat in section 10, wondering if he had one more magic swing in his bat to send his Magic City fans into an absolute frenzy. Alas, Miami mop-up man John McMillon made quick work of him, striking him out on four pitches. I strolled down the aisle toward field level to see if I could say “hi” to Nick from Arizona, but the ushers patrolling the entrance to the park’s best and closest ring of seats take their job very seriously. I waited it out a few rows up while the Marlins mounted a comeback against Diamondbacks closer Paul Sewald that ultimately fell short. Final score: Snakes 9, Fish 6.14

Once the guardian of the good seats let me by to see Nick, we chatted for a few minutes about rookie’s big night: 2-for-4 with a grand slam, six runs batted in and a stolen base just for good measure. Nick told me that he went to guest services before the game and they gave him a button to commemorate finishing the 30 ballpark tour at loanDepot park. I thought that was pretty cool and filed that info away for when I would be finishing up my own tour in New York 11 days later.

As I walked away, I lingered in the area behind the dugout for a little while as the Adrian Del Castillo cheering section hung around for his post-game interview with the Diamondbacks TV broadcast field reporter. No one there was ready for the night to end, for the glory to fade, for the pride to subside. When the interview wrapped up, the fans burst into applause, showering Del Castillo with adulation one last time before he stepped down into the dugout on his way back to the clubhouse. He was home. Soon I would be too.

NEXT GAMES:

Philadelphia Phillies at Atlanta Braves, Wednesday, Aug. 21, 7:20 p.m. EDT, Truist Park

Toronto Blue Jays at Boston Red Sox, Thursday, Aug. 29, 7:10 p.m. EDT, Fenway Park

St. Louis Cardinals at New York Yankees, Friday, Aug. 30, 7:05 p.m. EDT, Yankee Stadium

This facility has changed names more than criminal/baby oil enthusiast Sean Combs:

Joe Robbie Stadium (Aug. 16, 1987 – Aug. 25, 1996)

Pro Player Park (Aug. 26, 1996 – Sept. 9, 1996)

Pro Player Stadium (Sept. 10, 1996 – Jan. 9, 2005)

Dolphins Stadium (Jan. 10, 2005 – April 7, 2006)

Dolphin Stadium (April 8, 2006 – May 7, 2009)

Land Shark Stadium (May 8, 2009 – Jan. 5, 2010)

Dolphin Stadium (Jan. 6, 2010 – Jan. 19, 2010)

Sun Life Stadium (Jan. 20, 2010 – Jan. 31, 2016)

New Miami Stadium (Feb. 1, 2016 – Aug.16, 2016)

Hard Rock Stadium (Aug. 17, 2016–present)

This is my new favorite historical code word for “shitter.”

Yes, this is the stylized capitalization they chose to go with.

Progressive Field in Cleveland is the smallest at 34,830, the result of renovations over the past decade that removed more than 10,000 seats. Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg technically had a capacity of 25,025 for the 2024 season, but only because they entirely closed off the upper deck seating: if it were re-opened, The Trop could have accommodated about 41,000 fans. Of course, in 2025, both the Rays and the A’s will play in minor league ballparks in Tampa and Sacramento, respectively, with capacities closer to 11,000, making those temporary homes the smallest by far.

And now functionally destroyed by Hurricane Milton. The proposed new ballpark in St. Petersburg’s Gas Plant District won’t be ready until the 2029 season, if it happens at all. Negotiations among the team, city and county over ballpark construction funding have been contentious, to put it mildly. The Rays will play at least one season across the bay in Tampa at George Steinbrenner Field, the spring training home of the New York Yankees, but where they’ll end up for 2026 and beyond is anyone’s guess.

Named for the local area code. Glad they’re not 809.

Don’t do this. Even I wouldn’t do this, and baseball, hot dogs and beer are, like, my three favorite things.

That dog is Doris: she’s a six-year-old mutt we adopted from the Franklin County Dog Shelter in October. She’s the best dog ever. All dogs are the best dogs. But ours really is the best.

I was unable to walk the upper concourse as the team closed that seating level due to their expected low attendance.

This display used to be much larger: when former Marlins owner Jeffrey Loria sold the team in 2017, he donated a majority of the collection — about 900 bobbleheads — to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown.

No vuvuzelas though. The team has a strict zero tolerance policy against droning instruments.

loanDepot park does allow re-entry if you want to visit the big store during the game, but you do have to jump through some non-literal hoops to make it work.

That performance prompted me to pick him up for my fantasy roster, as I was in need of a short-term catcher to plug into my lineup.

My home team winning streak that dated back four weeks to Kansas City’s 10-4 victory over these same Arizona Diamondbacks was finally snapped. Home teams are now 16-13 on the Bleachers and ‘Bleeds tour.

"Don’t do this. Even I wouldn’t do this, and baseball, hot dogs and beer are, like, my three favorite things."

I feel like if it's to be done, doing it for the tidy sum of 72 smackeroons is Deal of the Century kinda money. Not sure I could make that happen at a Staten Island Ferryhawks game!